Raising Venture Capital for your startup looks like an insider’s game from the outside. It isn’t clear how to get into this network. Once you pitch, it’s unclear on what it takes to convince someone to invest.

There are lots of tactics to discuss here, but there is a very common misunderstanding about how VCs actually work.

How Normal Works

First, let’s talk about a normal investment. This might be a public stock or a house.

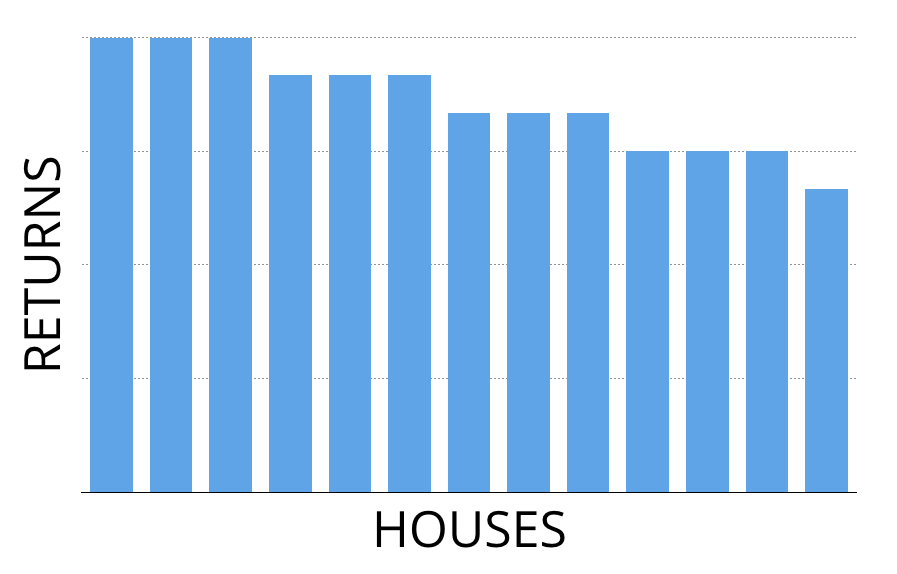

You want to minimize risk. You don’t want to lose your money. Ideally, you make a 5%+ annual return and go away happy. Here is what that looks like for a rising housing market where some houses do a bit better.

If you ask a normal person what a good investment looks like, they might describe a very high likelihood to return your money and make a bit more.

You can see this in aggregate too, in terms of economic growth rates. Look at all those single digits.

The problem is that VCs aren’t normal. So stop thinking like you’re pitching a normal investor.

Abnormal Returns: Power Laws

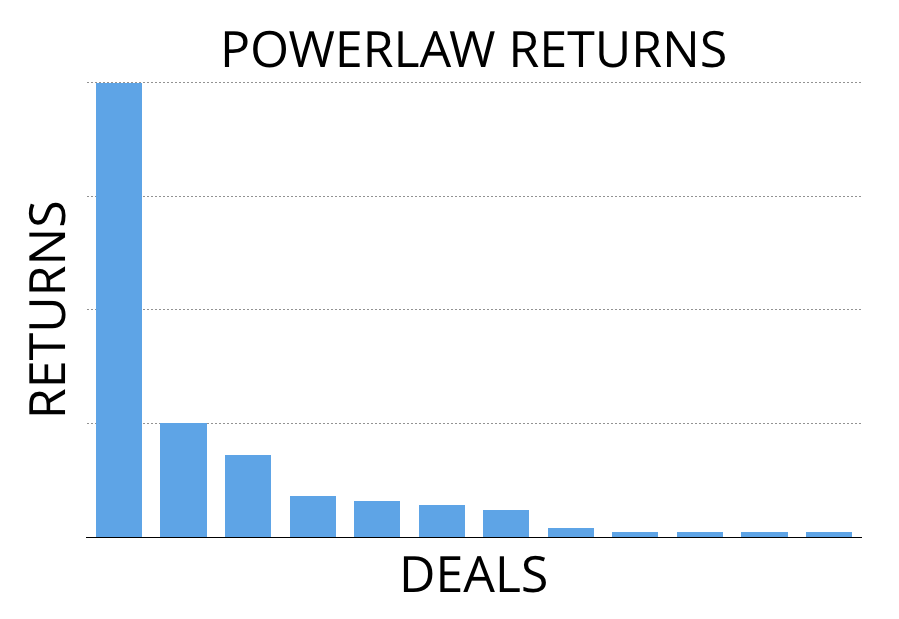

If you took a VCs entire portfolio of investments, and sorted them by the return on investment, what would that look like?

The secret is that half of the total returns probably came from their single best investment. That investment might have returned 100X the original investment. So compare that 5% to this 10,000% (over a few years).

Then, of the remaining portfolio, another half came from the next two top investments. Here is what that looks like.

There are a few things to notice about this graph.

First, the length of the tail of failed investments doesn’t matter. VCs can lose all their money in an investment, and it doesn’t matter for their fund.

Second, the height of the top few investments will determine the returns for the whole portfolio. VCs must be in the best deals, or they won’t make money as a fund.

The fear of missing that top deal is real. Let’s add a big missed deal to the graph above to compare the cost:

Not By Choice

I used to think this setup was weird. Why don’t VCs shoot for a higher average return with a higher win rate but a lower variance?

The interesting thing about these power law returns is that you don’t make them entirely by choice. If you pick investments with some thesis, and sort your returns, they’ll look like this shape. I think this has to do with the way technology helps create defensible businesses to the exclusion of other companies.

Ignoring the shape of these returns isn’t optional.

Downstream Behavior Explained

Knowing this helps explain so much of a VC’s behavior.

They aren’t looking for a guaranteed $1M, they want a *chance* at $1B or $100B. This is really weird, because software business that are profitable might not be fundable.

Investments that go to zero don’t matter. VCs would rather swing for the fences and strike out. Practically, after a VC invests, they’ll care about getting the money back. But this isn’t going to make or break their fund.

Missing the top is the main risk for a VC. It’s an opportunity cost. That is a powerful idea because you can position your company appropriately knowing this.

This also explain why deals get hot. VCs think that a competing firm knows something they don’t. They aren’t punished for a deal going to zero, but they’ll suffer if they miss out on the head of this power law.

The reverse is also true, with cold deals that can’t seem to close. You’d think VCs are independent thinkers, but the lack of interest from other VCs can really hurt your fundraising.

Another thing that happens with these returns is that they are by definition exceptional. So there is shockingly little data on what makes the best deals. This is really tricky because you’re looking for what the best deals looked like when the companies were just getting started. The result seems to be a lot of ink spilt on signals that are probably noise.

So if you’re pitching VCs, don’t focus on the immediate profit you can make. Focus on how there is a chance you’re going to make a home run. Talk to a bunch of firms in parallel to create a fear of missing out. Traction to date matters, and so does selling your vision for the future.